The Reformation as a turning point and a beginning

From the mid-1520s, the Reformation plunged the university into an existential crisis. In 1532, its relationship with the city authorities was reorganized, laying the foundation for a long-lasting upswing throughout the sixteenth century.

The early conflicts of the Reformation movement also caused internal disputes at the university. In 1522, during Lent, university members participated in a demonstrative meal of roasted pig at Klybeck Castle and tried to force the election of a new rector. As an institution, however, the university proved to be a stronghold of Reformation opponents: Bonifaz Wolfhart, for instance, lost his teaching license for breaking the Lenten fast, and the rector during winter semester 1522/23, Johannes Romanus Wonnecker, used his entry in the matriculation book to make an elaborate complaint about the troublemaker Martin Luther.

In the following year, 1523, when four professors made accusations against two popular Reformist preachers (Lüthart and Konrad Pellikan) during an inspection by the head of the Franciscan province, the City Council revoked their salaries and appointed Pellikan and Johannes Oekolampad (later a figure in the Basel Reformation) as theology professors in their place. The university opposed this move by continuing to appoint so-called followers of the traditional faith to faculty positions. Furthermore, the theologians refused to accept Oekolampad and Pellikan into the faculty, and the rectors eloquently lamented the unrest of the times.

The university at the height of Reformation turmoil

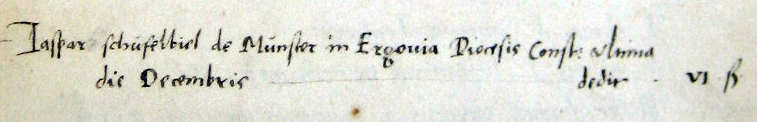

In subsequent years, the university increasingly split into two factions. As supporters of the Reformation, Oekolampad, the professor of medicine Oswald Baer, and the professor of the liberal arts Torinus stood opposed to the skeptics and followers of the traditional faith – the theologian Ludwig Baer, the jurists Catiuncula and Amerbach, and Sichart and Glarean, who had reconsidered their support of the Reformation following the Peasants’ War. The conflicts continued to escalate; matriculations dropped drastically, leading to only one student – Caspar Schüfelbiel from Münster in Aargau – enrolling at the University of Basel in December 1528.

At the height of the Reformation turmoil in the city, in the spring of 1529, the majority of professors and students most likely joined the cathedral chapter in leaving the city and moving to Freiburg. On 14 June 1529, the deputies representing the City Council seized the university’s scepter, seal, statute books, documents, and treasury, depriving it of the central foundations for its regular functioning. It was no longer able to issue valid diplomas and documents, or to exercise legal jurisdiction through university courts. At the same time, the council prevented the opponents of the Reformation from relocating the university itself elsewhere.

However, contrary to the view predominating in older research, university operations never seem to have completely ceased in the following years. At least some teachers continued to receive their salaries. Moreover, in 1531, during the so-called interregnum, the first public anatomical dissection took place at the Faculty of Medicine under Oswald Bär, who was the last rector before the Reformation won the upper hand in Basel in 1529 and the first after the “reopening” of the university in 1532. This marked the beginning of a long success story for the Faculty of Medicine, which, along with the Faculty of Law, made Basel a highly sought after university at the cutting edge of contemporary trends, especially in the second half of the sixteenth century. Yet this future was far off at the time.

During the interregnum, probably in 1531, a legal report – likely authored by Johannes Oekolampad – was prepared discussing the reorganization of the university. It called for members of the Faculty of Law to intensify their study of sources and reduce their reliance on numerous commentaries, while members of the Faculty of Medicine were to focus more on practical exercises. Fees were to be lowered, and the costly rituals involved in awarding academic degrees were to be abolished. The report declared that the primary concern of the Reformed university was to educate good Christians, in close connection with preparation for a practical profession. This new practical orientation, together with the subordination of the university to Christian authorities, was to become a key feature of the post-Reformation university and its revised statutes.

The reopening of the university and its integration into the city’s Reformed polity

The transitional period between the old and new order for the university ended with the enactment of new statutes, ceremoniously announced by the newly elected rector, Oswald Bär, and several university members on 20 September 1532. On 1 November, the rector then officially invited students to enroll at the reopened university, explicitly mentioning professors Paul Konstantin Phrygio, Bonfiacius Amerbach, Sebastian Münster, Simon Grynaeus, Albanus Torinus, Wolfgang Wissenburg, and Simon Sulzer.

Notably, the new statutes did not mention the university’s former rights and privileges but instead completely reconfigured the relationship of the university to the city. Now, it was the City Council that issued statutes for the university, effectively subordinating the institution to municipal authority. Accordingly, the university largely lost its privileges: its tax exemptions were abolished, leading to endless disputes between the university and the city court, as well as the council. The university’s legal jurisdiction was limited to monetary debts and its self-administration was curtailed.

It was likely for this reason that university operations were then slow to get going. It was not until 1536 that the Faculty of Liberal Arts appears to have regained full functionality. In the following years, further reforms were discussed, and the faculties prepared corresponding reports. In 1538, the Senate approached the City Council, requesting that it regain its old privileges to manage the university. This led to another revision of the statutes in 1539, in which the council accommodated the university in all aspects except for the appointment of new professors, which remained with the city’s deputies; in matters concerning teaching, however, the university regained full independence. The fundamental shift from the medieval university, which was a spiritual institution whose academic work was centered on the study of scholastic theology, to an organization that served the Reformed state by training pastors, officials, judges, doctors, and teachers, was irreversible. Accordingly, the university and the council also agreed to integrate the clergy from the Faculty of Theology. Furthermore, only those professing the Reformed faith could be appointed as professor.

With the Reformation, the university had become a state institution. This transition was soon augmented by a spatial expansion: in 1538, the university took over the dissolved Augustinian monastery, henceforth called the Upper College, while the original building on Rheinsprung Street was now referred to as the Lower College. Apart from the relocation of the library in 1662 from the Lower College to the address known as Zur Mücke, these two main university buildings remained essentially unchanged until the nineteenth century.